As I’ve written about before, I maintain a fondness of the Minecraft mod ComputerCraft. For those unaware, this adds programmable computers to Minecraft, accompanied by a whole host of peripherals (and the ever-so-lovely turtles).

As development of the original mod has dwindled, I’ve begun to work on a fork of ComputerCraft known as CC: Tweaked (or CC:T for short). Over the last 18 months, we’ve added all sorts of fancy features, like full-block modems, file system seeking and the ability to use pocket computers like maps

While there’s been a fair few changes to the visible gameplay, I’ve also done a lot of work on ComputerCraft’s internals. These sorts of changes shouldn’t have any serious user-facing impact, but should still help improve one’s experience with the mod. I thought it’d be fun to go over some of the recent improvements that have been implemented. So here goes…

TLDR

Honestly, this is a bit of a behemoth of a page so I can’t blame you if you don’t want to read it all. Here’s a summary:

- “Unlimited” Lua call stack for the Lua VM.

- Coroutines are lightweight again. Should reduce resource consumption, and maybe memory usage too.

- Computers can be interrupted. Should reduce latency when you’ve got someone hogging the computer thread.

Cobalt

At its heart, ComputerCraft is just a wrapper over a Lua VM. Instead of using the reference implementation, PUC Lua, we use a Java-based implementation known as Cobalt. This is a fork of LuaJ 2, with a few changes to ensure it is thread-safe, provides good error messages, and some minor bug fixes.

Both Cobalt and LuaJ are rather tied to Java’s execution model. A Lua function call translates to a Java function call, a coroutine translates to a thread. While this does make it easier to work with than Lua’s standard API, it does also introduce some limitations.

The interpreter loop

As each Lua call translates to a Java call, the Lua call stack is bounded by the size of Java’s stack. Given the Lua interpreter ends up consuming a fair bit of stack space, this ends up allowing a call depth of about 256. While this tends to be enough for most cases, some programs (most notably LuLPeg) require much more than that.

Most other Lua implementations do not suffer this problem: when the interpreter calls another interpreted function, we just replace the existing interpreter, instead of calling a new one. Likewise, returning from an interpreted call finds the previous Lua function on the stack and the interpreter will resume into that.

This is actually incredibly simple to implement1, and means we can increase our stack depth from 256 whatever we want! In practice, this is capped at 32767, as any well written program should fit within this limit, but badly written ones won’t run until the memory is exhausted.

Error propagation

This is a small change, but an interesting one (interesting is pretty subjective here). LuaJ and Cobalt would push a Lua frame when calling a function, and popping it when returning, even if that function errored. However, PUC Lua does not pop frames when a function errors - it is instead done by the error handler. This means a couple of things:

- If you’ve got a debug hook, functions which error will not receive a

returnevent. - When you’ve no error handler, the stack will not be unwound. Which means you can inspect the stack of crashed coroutines.

Again, the change was pretty small, but well worth it. Not only are we closer to original Lua, it means we can run xpcall’s error handler within the definition of xpcall, rather when the exception is first caught, making handling a little easier to trace.

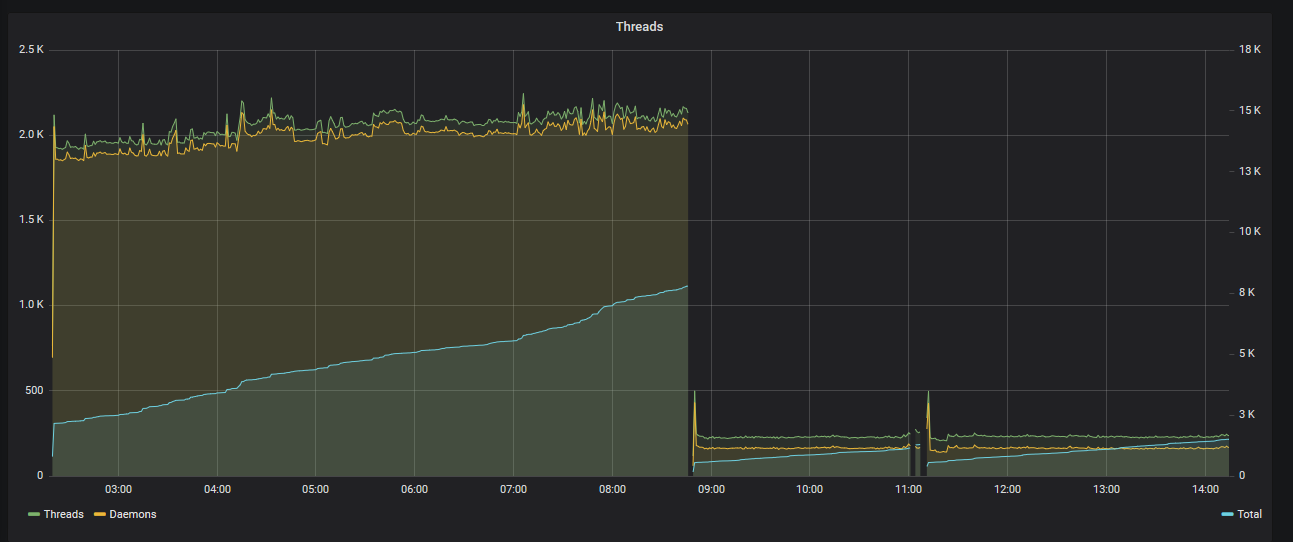

True green-threads

In LuaJ, each coroutine is backed by a Java Thread. Most of the time, this isn’t an issue, but there are a couple of extreme cases where it begins to cause problems. Back in November, the SwitchCraft server was repeatedly dying due to the sheer number of threads which ComputerCraft had created (250k, at a rate of 50/s). I’ve written about this previously and the steps we took to mitigate this.

However, this doesn’t really address the underlying dilemma. Coroutines, which are meant to be used as a lightweight way of doing concurrency are really not. One should be comfortable that creating thousands of coroutines per second is not going to have an adverse effect on performance.

The solution, as always, was to move Cobalt closer to PUC Lua. Yielding, instead of sending signals between threads, now throws an exception. This unwinds the whole Java call stack to some top-level interpreter, which then switches control over to another coroutine.

While this sounds pretty simple in practice, there are all sorts of problems which come along with this. The biggest of these is ComputerCraft itself. The API makes an assumption that yielding a coroutine will block, not doing anything until it is resumed again. While this is true under the old threading model, it is no longer true under this “throw and switch” system.

The solution is to have a system which supports both: if we are able to unwind the stack, we should do so. Otherwise, we fall back to the original threading code. It ends up being a little bit of a messy system, but incredibly effective - SwitchCraft, with its 250 computers, went from 2000 threads to 50.

Better threading and preemption

One important thing to note about ComputerCraft is that, like a real computer, only one computer is doing one thing at any time. However, unlike a real computer, there’s no concept of preemption - one computer running for a long time will hold up all the others. In order to prevent this being too much of a problem, the Lua VM will throw an error after 7 seconds, and will be entirely killed after 8.5 seconds.

However, if one computer starts running for 7 seconds every time it is resumed, you’re going to start having problems - every key press, mouse click, and the like will take an awful long time to be processed. CC:T somewhat improved this by running computers on multiple cores - now one badly behaving computer wouldn’t cause issues, but once you have more than a couple, problems start to arise.

As part of our above Cobalt changes, we also introduced the ability to “suspend” the Lua runtime. This acts a little bit like yielding, but instead of passing control back to the parent coroutine, it yields straight to ComputerCraft. This is fantastic, as it means we can invisibly pause the computer at any point, let another one run, and resume it afterwards.

In addition to that, we’ve also introduced a computer scheduling system. Inspired by Linux’s CFS, this pretty much just sorts computers by how long they have executed for, prioritising those which have done less. As a result, computers which do little work will respond to user input almost immediately.

In practice, these changes won’t make any difference most of the time. Generally, programs are pretty well written and so computers are relatively responsive. However, when you’ve got badly written (or malicious) programs in play, it makes a world of difference - one is able to interact with a computer with negligible latency!

I feel it’s also worth mentioning that as part of these changes, we rewrote the entire threading system in an effort to make it simpler and more robust. Not only has this fixed a rather annoying deadlock when killing a computer, we now use half as many threads within the executor2.

Where now?

Honestly, I don’t quite know. I started work on some of these features two years ago, and I can’t think of many other changes I’d like to make of this magnitude.

One thing I’ve put some thought into is scheduling and limiting work done on the server thread. While this isn’t especially useful for vanilla CC, extension mods such as Plethora can do a lot of work on the server thread and can directly contribute to lag. Ideally, we could limit the time CC uses every tick, making sure badly behaved computers don’t cause issues for everyone.

On a rather different vein, I’ve been thinking about how we handle documentation. The current situation is a little dire, so I’d really like to see some solutions which make everything more maintainable. If you’ve any ideas on this (or anything else!) do drop me a line - I always want more ideas from the community.

I guess I should probably be looking into persisting computer state too…

You can see the PR and associated diff. The commit of interest (

9b6af10) is only so big thanks to an extrawhileloop causing the indentation to change.↩︎The previous implementation had managers and executors. We’ve replaced this with executors and 1 monitor. Honestly, this shouldn’t make any difference, unless you had an extremely high thread count.↩︎